An international consortium announced Tuesday that France would be the site of the world's first large-scale, sustainable nuclear fusion reactor, an estimated $10 billion project that many scientists see as crucial to solving the world's future energy needs.

"It is a great success for France, for Europe and for all the partners in ITER," President Jacques Chirac said in a statement released after the six-member consortium of the United States, Russia, China, Japan, South Korea and the European Union chose the country as the site for the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor.

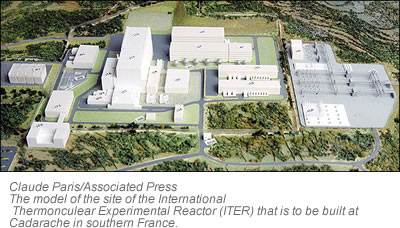

Japan, which had lobbied hard for the project, dropped out of the bidding in the last few days and ceded to France. The consortium agreed in Moscow to build the project at Cadarache in southern France.

Nuclear fusion is the process by which atomic nuclei are forced together, releasing huge amounts of energy, as with the sun or a hydrogen bomb. The process has long been studied as a potential energy source that would be far cleaner than burning fossil fuels or even nuclear fission, which is used in nuclear reactors today but produces dangerous radioactive waste.

While the physics of nuclear fusion have long been understood, the engineering required to control the process remains difficult.

The logistics of coordinating construction in a six-member consortium has presented an even bigger challenge. The project was started in 1988 but bogged down in bickering over where the reactor's design team would be based. A compromise split the team between Japan, Germany and the United States, but the consortium struggled over where the reactor would be built.

Canada, Spain, France and Japan were originally in contention for the reactor site, but a December 2003 ministerial meeting to pick a winner ended in a deadlock, with the United States, Japan and South Korea backing the Japanese site and the other three consortium members pushing for the site in France.

Recently, Japan agreed to relinquish its bid in return for the consortium's commitment to build a $1 billion materials testing center there.

The consortium also promised that any subsequent fusion reactor built by the consortium would be built in Japan. It is a significant concession, because the first reactor is only a demonstration plant meant to prove that fusion can be harnessed as an economically viable energy source. A second reactor would probably be a prototype meant for commercial power generation.

With the agreement, the consortium can now proceed with the drafting of a deal on the construction and operation of the reactor. ITER officials said they hoped that the accord would be signed by the end of the year, allowing work on the reactor to begin next year and ground to be broken at the Cadarache site in 2008. Current plans foresee the reactor operating in 2016.

Construction of the reactor is estimated to cost $5 billion, with its operation costing another estimated $5 billion over 20 years, according to ITER. The host country is expected to cover half of those costs, with the other five partners each paying 10 percent. Those numbers are based on current dollars, however, meaning the actual cost of the reactor will be much higher by the time it is completed.

Many experts also predict that construction could take much longer than now foreseen given the difficulty of coordinating multiple suppliers of costly and highly technical components in many countries. The agreement leaves open the possibility that still more countries may take part in the project. India, for example, has expressed interest.

The final agreement is expected to include provisions that would require consortium members that cause delays to pay compensation.

The fusion project has stirred controversy since it was first proposed in the 1980's, with many scientists arguing that such "big science" will rob financing from the "little science" of individual researchers who have often produced the world's most striking scientific breakthroughs.

But criticism has been drowned out by the growing recognition of fusion's potential as a solution to the world's looming energy crisis.

"We all know oil and gas depletion will start in 2030 or 2035," said Peter Haug, secretary general of the European Nuclear Society.

He said most experts agreed that because of technical difficulties, renewable energy sources like wind or solar power would never provide more than 15 or 20 percent of the world's energy needs. There is enough coal in the earth to keep the world running for centuries, but at an unacceptable environmental cost. As oil and gas fields peter out, Mr. Haug and others say, the world will be forced to turn to nuclear energy.

"We don't think fusion will remove fission from the production scheme," Mr. Haug said. "But it will probably be used along with fission because of the growing energy needs of man."

Still, few scientists expect a fusion reactor to generate commercially viable electricity before mid-century, if by then.

In principle, using fusion to produce energy is easy: take hydrogen atoms and press them together to form helium. The helium is a bit lighter than its constituent hydrogen pieces, and by Einstein's e="mc2" equation, that tiny change in mass results in a large release of energy.

At the center of the sun, where temperatures reach nearly 30 million degrees Fahrenheit and hydrogen atoms are pushed together at ultra-high pressures, fusion generates light and heat. But turning fusion into a viable source of energy requires figuring out how to recreate on Earth the conditions at the sun's heart.

Instead of ordinary hydrogen, fusion reactors use heavier versions, known as deuterium and tritium, that fuse together more easily. Experimental fusion reactors have been able to heat gases to temperatures of hundreds of millions of degrees. The harder task, however, is confining the hot gas.

ITER follows the same approach used by most large-scale fusion experiments since the 1970's, using doughnut-shaped magnetic fields to confine the gas, but it will be the first large enough to explore how well fusion reactions can be sustained.

In order to succeed, the ITER project must demonstrate that it can create a fuel cycle in the reactor that will produce excess tritium, the reactor's fuel, from a "blanket" of lithium lining the reactor chamber. As neutrons thrown off from the fusion reaction strike lithium atoms, they produce tritium. But in order for the reactor to be viable, consortium officials say, the reactor must produce more tritium than it consumes.

Even fusion proponents concede that the process is decades away from practical use. A timeline published on ITER's Web site foresees a larger demonstration project that would begin operating around 2030. A commercial fusion reactor would follow around 2050.

ITER's interim leader, Yasuo Shimomura, said the project's next step would be to appoint a director general who could start the complicated procurement process.

The consortium has already spent $700 million on scale models of the reactor's major components, and "in this sense, there is no fundamental technical problem," Dr. Shimomura said in a phone call from ITER's offices in Garching, Germany. "But the machine is very complicated, and the procurement will be done between six parties, and this is not a small experimental device, it is a real nuclear device, so quality control will be very important."

In the meantime, the fusion project means money for the industries and scientific sectors contributing to it. Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin of France said it would create 4,000 jobs and bolster research and development there.

"It's brings us great joy and great pride," said Pascale Amenc Antoni, director of the French Atomic Energy Commission's Cadarache Center, where the reactor will be built. She said it also recognized the work the center has already carried out at its nuclear fusion research facility.

Kenneth Chang contributed reporting from New York for this article.