Just days after the fire at the Casino Royale, authorities captured five suspects, one of whom was a state policeman. Officer Miguel Angel Barraza Escamilla later admitted to investigators that he was a member of the Zetas. Investigators told the press that he had various jobs, including as a lookout during operations like the tragic shakedown at the Casino Royale and driving members of the criminal gang in stolen vehicles.

Barraza also gave authorities information that allowed them to paint a picture of the top levels of the organization in the area. (A few days after his arrest, suspected Zetas killed his father, half-brother and godmother.) At the top of the cell, authorities put Francisco Medina Mejia, alias “El Quemado.” Authorities said that Medina answered to Carlos Oliva Castillo, alias “La Rana,” who answered to Miguel Trevino, alias “Z-40,” now the organization’s number one, who is allegedly based in Nuevo Laredo, along the US border. Oliva Castillo was captured in the neighboring state of San Luis Potosi in October 2011, while Medina was killed in a gunfight with Mexican soldiers in April 2012.

Below Medina were several lieutenants, including Jose Alberto Loera Rodriguez, alias “Voltaje.” Loera’s presence caused a stir in Mexico since he was a former professional wrestler. He was captured in early October 2011. When they presented the muscular 28-year-old with his shock of red hair, authorities explained that Loera managed about 40 lookouts. Two others who were captured were in their teens and were presumably working as lookouts, although authorities said they were captured with high-powered weapons. In all, 18 people have been captured since the Casino Royale tragedy, from lookouts, to mid-level lieutenants, to police, giving a useful view of how the Zetas have organized themselves in the area and how much the city is worth to them.

How Many Are There?

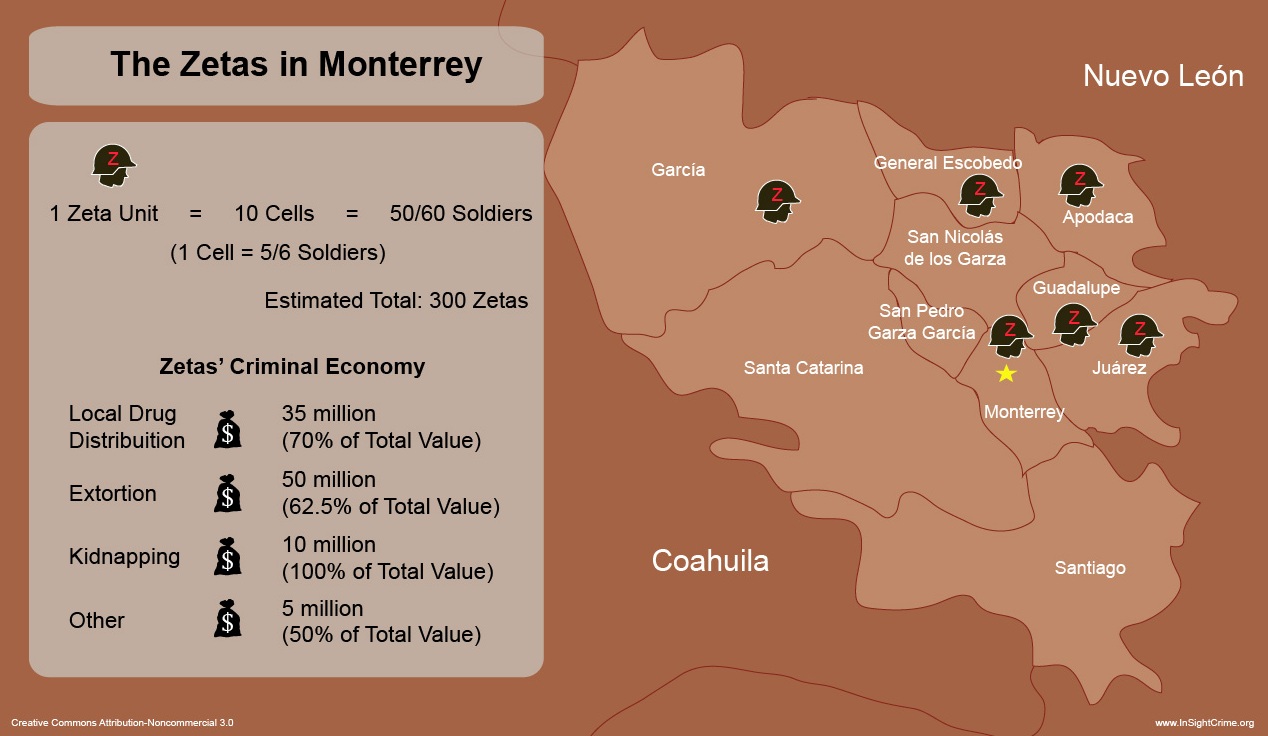

The Zetas are broken down by units. Each unit is responsible for a specific geographic area. In Monterrey, these geographic areas are related to municipalities, although the boundaries may not always correspond exactly. (When I speak of Monterrey or the area, I am talking about "Metropolitan Monterrey," which, as defined by the government statistical body INEGI, includes the municipalities Apodaca, Garcia, General Escobedo, Guadalupe, Juarez, Monterrey, San Nicolás de los Garza, San Pedro Garza Garcia, Santa Catarina, and Santiago.) For example, there would be a unit for nine of the ten municipalities that make up Metropolitan Monterrey, with San Pedro Garza Garcia being the exception as it is territory of the Zetas’ allies, the Beltran Leyva Organization.

The size of the units depends on the size of the area, but according to international and local law enforcement, the units tend to have between 50 and 60 core soldiers. They are broken into “estacas,” or cells, in homage to the Zetas’ military origins. These cells are small enough to be transported in vehicles, i.e., five or six men per mobile column.

A year ago we could have multiplied this number by nine municipalities, and the estimate of Zetas soldiers would have been close to 500 in the area. However, the Zetas have lost ground in recent months. Even before the death of their maximum leader, Heriberto Lazcano, in October 2012, the Zetas were having difficulty maintaining control due to sustained attacks by their former bosses, the Gulf Cartel and their new allies, the Sinaloa Cartel.

The death of Lazcano may accelerate this deterioration further. Lazcano was a mythic figure that seemed to hold this disperate organization together. What's more, the Zetas were already showing signs of fraying at the edges. If we assume there is still command and control of the Monterrey-based Zetas, they would have close to 300 fighters in at least six municipalities, mostly the northern part of the city.

These core soldiers have recruited local gang members to work with them. The number of gang members collaborating with the Zetas is much harder to calculate. One member of the Monterrey security forces broke it down for InSight Crime by “colonias,” or neighborhoods. He estimated 10 per colonia, and said that just counting the poorest neighborhoods means there are about 2,000 collaborators. If he adds other, marginal colonias, the estimates reach closer to 3,000.

That does not mean, however, there are between 3,000 and 4,000 “Zetas” in Monterrey. Not all the gangs work for the Zetas and not all those who do are Zetas. They are what locals like to call “Zetillas.” Their main job is to be the “halcones,” or hawks, the lookouts for the organization. But they also collect extortion quotas and manage the drug distribution centers in the neighborhoods. They may be called to do other jobs such as block roads, distract military forces, guard safe houses, or assassinate a rival. But the high number of gang collaborators is a reflection of their low status within the organization. With few exceptions, they are, to be blunt, expendable.

The part of the structure that is not expendable, however, is the police. Like criminal organizations throughout the world, the Zetas rely on the police. In the broadest sense, the police are the Zetas’ top-cover: They ensure that the Zetas can operate in the geographic area under their jurisdiction, hence the Zetas’ tendency to assign a cell to a specific municipality.

Specifically, police have many jobs. They can clear an area of rivals and fill an area with friendly law enforcement. They can hold or accompany illegal goods. They can seize goods from rival organizations; they can get Zetas’ goods that have been seized released from custody. They can provide weapons and ammunition. They can thwart an investigation against the Zetas, or push an investigation against a rival. And they can alert the organization to the security forces’ movements, positioning and strategy.

This top-cover and logistical support network is distributed mostly between the multiple police agencies in the area. In Monterrey, there are municipal and state police. But there also transit police, which provide critical backup and intelligence about the movement of military convoys and the federal police.

How many police work with the Zetas is difficult to know. The government has gone through numerous purges, expelling over 4,000 police in the state of Nuevo Leon, the vast majority in Monterrey, yet penetration remains a problem. As recent as January, the military arrested 106 Monterrey police. But these broad sweeps do not always mean that the entire police were, or are, Zetas’ collaborators. What’s more, the participation of individuals within the police varies. Some are deeply entrenched in the Zetas’ structure. Others have limited roles or simply keep quiet about who is who and their activities. And often, it is as important to control several key positions within the police, as it is to have numbers.

Finally, there is the Zetas’ logistical infrastructure to consider: the people who fix cars for them, handle their money at the banks, find their safe houses, get them fake IDs, buy their weapons or steal cars for them. In Colombia, the calculation is that for each guerrilla fighter in the field, there are three who provide logistical support of this kind. But this calculation is hard to apply to the Zetas. They are an urban-based group. Parts of their operational structure handle some of these jobs for them, so that reduces the number needed for logistics. In all, the Zetas appear to have a limited need for a vast logistical support team.

In sum, the structure of the Zetas in Monterrey is large, but it is made up of layers. Each layer has a different level of integration in the group. Speaking only of core members, the Zetas have close to 300 in Metropolitan Monterrey, not including police that play an active role in the operational side. The gang members number in the thousands, and while this is a tremendous source of crime and overall chaos in the city, these are not core members. As is increasingly evident, fewer and fewer of them have training. Lastly, we have a logistical network that is not Zeta per se but rather contracted by the group for specific tasks. The Zetas, then, have an infrastructure that includes close to 4,000 people. And just how they keep this umbrella organization together is the direct result of their criminal model of extracting everything they can from this city’s economy.

Monterrey’s Illegal Market Value

The Zetas are not like any other large criminal organization in Mexico. They are enforcers first, businessmen second. Their economic well-being is dependent on their ability to exert military power over the marketplace. They are less interested in controlling the distribution chains and more interested in controlling the territory in which the business is done. In these areas, they have established a monopoly on power and collect “piso,” or rent, on local drug trafficking activity, piracy, contraband, prostitution and other criminal activity. They also steal, extort legitimate businesses and kidnap.

The local drug market has been growing for the last 20 years in Mexico, but its rise has been especially pronounced in the last few years. Use of marijuana, the most popular drug after alcohol, and cocaine have been steadily increasing. In Mexico, cocaine use doubled between 2002 and 2008, according to the last survey by the government’s National Council Against Addiction. The numbers who said they did cocaine, 2.4 percent, is about half of what it is in the United States. (See report pdf) A quarter of those using cocaine said they were using crack. Women between the ages of 12 and 25 consumed more cocaine, crack and methamphetamine than other age brackets, the report noted.

The "prevelance" of cocaine use, 0.4 percent, is on a par with the world average, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and, as a state, Nuevo Leon ranks amongst the lowest in drug use. But as a municipality, Monterrey is amongst the highest in the country. In a 2005 survey by the council -- which focused on consumption in Tijuana, Ciudad Juarez, Monterrey and Queretaro -- over 10 percent of the respondents they had consumed some form of drugs. The highest use reported by any state in the 2008 report was 11 percent, according to the 2008 survey, which did not, unfortunately, break down the numbers by municipality.

The numbers are reflective of a larger trend in the region and in developing countries in general. Percentage-wise, Argentina has rates of use comparable to the United States. Brazil has close to one million cocaine users, putting it in a league with Spain and Great Britain in absolute terms. Countries with smaller populations such as Venezuela, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica and Haiti have also reported increases in consumption in recent years. This is something that worries international observers as well.

"Demographic trends suggest that the total number of drug users in developing countries would increase

significantly, owing not only to those areas' higher projected population growth, but also their younger populations and rapid rates of urbanization," the UNODC wrote in its 2012 annual report. (See report pdf)

The Zetas have taken advantage of this burgeoning market and possibly had a role in fostering it. State and city officials told InSight Crime that, by using local gangs, the group has increased the number of distribution points. They tag their product and dispatch their soldiers and minions to ensure that the users are consuming it. Failure to smoke Zeta-stamped crack could result in a severe beating, the officials said.

Estimations of how much this market is worth to them vary. Some say drug sales in Monterrey reach the $8 million per week mark. This somewhat unscientific number comes by calculating the number of “tiendas,” or distribution points, in the city and assigning a modest number of sales to each, and leads to a conclusion that may be difficult to sustain but represents a starting point in the discussion: that Monterrey's drug market could be worth nearly $400 million annually.

This is an overestimation. According to Alejandro Hope, who drew from one Zeta leader’s confession about his operations in Veracruz, the entire Mexican illegal drug market is worth close to $950 million per year. Of this, Monterrey, by population alone (4 percent of Mexico’s total population), would command closer to $40 million. Since Monterrey is a larger than average market, we can round this up to $50 million. Assuming the Zetas control 60 percent of this market, that gives them around $35 million in annual revenue from local drug trafficking.

These same soldiers and minions are collecting “piso” from the illicit and licit businesses. Obviously, there is little reliable data on these illicit markets. However, we can use the size of the informal economy to obtain an idea of the size of the potential revenue source. According to a 2011 INEGI report, 23.4 percent of Monterrey’s labor force, or just under 400,000 people, are in the informal market. That does not correspond to a quarter of the city's economic power, but it does create ample opportunity for extortion.

On the legitimate business side, the size of the market grows. The state of Nuevo Leon is responsible for 7.5 percent of the GDP of the country, behind only Mexico City and Mexico State. It has the country's second largest industrial and construction sectors, and comes top in the amount of truck traffic.

But calculating potential and actual revenue from licit businesses is as challenging as for the illegal drug market. CISEN estimates that businesses cannot afford more than $10,000 to $15,000 per year, and that most pay much less. Indeed, 92 percent of Nuevo Leon companies have less than 50 employees; their earnings represent just 6.3 percent of the state's total earnings. And while there are 129,000 "economic units" that make for potential targets, the average unit only makes $22,384 per year.

How many of these businesses face demands from criminals is unknown, and crime statistics do not help us much either. National statistics show that Nuevo Leon had a steady number of reports of extortion between 2008 and 2011. Anecdotally, however, extortion was on the rise. And traditionally, extortion is one of the least reported criminal acts in Mexico.

If we assume then that the Zetas extort 1 of every 10 businesses in the state, taking, on average, 10 percent of all revenue (or about $2,200) that would mean they would be making close to $30 million in annual revenue from this activity. Combined with what they are taking from the black market operators, and we have between $30 million - $50 million in potential extortion revenue from Monterrey.

The Zetas are also involved in kidnappings. There were 43 reported kidnappings in Metropolitan Monterrey through November 2012. (Government crime report pdf) The average ransom is near $15,000, which gives us a revenue of $650,000. Kidnapping is also greatly underreported. Some groups estimate the so-called "cifra negra," or unreported number, could be as much as 15 times higher than that reported to the authorities. Assuming this is true, kidnapping revenue in the Monterrey area could then represent up to $10 million in earnings per year.

There are numerous other, less lucrative businesses. Some Zetas may also be involved in piracy or contraband, or a combination of the two. They may also make money from theft and resale. As is apparent, breaking down just how much money is collected from these activities and how it is distributed is complicated, which is why the Zetas have split their accounting arm from their military arm. These accountants keep detailed ledgers, but that still may not account for the different ways that the Zetas make money from Monterrey, especially as these revenue streams have moved into controlling actual distribution of illegal goods.

Take, for instance, the Zetas' business with local nightclubs, bars and restaurants in Monterrey. This relationship began when the Zetas displaced the local police from their long-time perch in the "Zona Rosa" and began collecting their own "piso" from bar, restaurant, massage parlor and nightclub owners. These businesses were willing to pay because initially there were benefits -- namely extra hours, no oversight of underage drinkers or expired liquor licenses, and hassle-free contraband alcohol. Soon, the prices increased and the line items multiplied. The Zetas took control of the contraband products, forcing these businesses to buy directly from them. They also allegedly forced the businesses to pay for the licensing through them. So what was a one-time "tax" under the police became a series of increasingly onerous expenses under the Zetas. Many subsequently went out of business or left the area.

The same process appeared to be swallowing the casino businesses in the area. What may have begun as a one-time tax by politicians for the gambling licenses was becoming a multi-item budget buster with the Zetas involved. In this case, however, it is not at all clear that the Zetas were the beneficiary of every line-item. Just days after the casino debacle, La Reforma media published a video in which the brother of the Monterrey mayor is collecting a large sum of cash from another casino. The mayor defended his brother, arguing that he was collecting money for the cheese that he sells to the casino.

_______

In sum, if we break it down by business -- local drug trafficking, extortion of the black market, extortion of the legal markets, kidnapping and other -- we can see that Metropolitan Monterrey is worth up to $150 million per year and up to $100 million per year to the Zetas. This excludes the value of the city in terms of money laundering and as a storage and embarkation point for illegal drugs going to foreign markets. It also omits the other logistical and economic opportunities that the country's industrial hub offers, including development of legitimate businesses, control of local publicly funded development projects, and other activities.