For some, it is their association with an enemy gang. For others, it is their community work. Some flee sexual abuse, forced recruitment, or extortion. But ultimately, every one of the thousands of people displaced within Medellin faces the same grim choice: Lose your house, job, and community -- or lose your life.

In 2012, 9,322 people in Colombia's second-largest city registered as victims of intra-urban displacement -- when victims are displaced to a different part of the same city. Yet, it is hard to assess the true scale of the problem. Missing from the official figures is the population of hidden victims who circulate through the city's neighborhoods in an often futile search for sanctuary, too scared of reprisals to admit they have been displaced.

Behind the alarming statistics is the battle for control of the Medellin underworld waged by the fractured remains of the Oficina de Envigado -- the mafia that has controlled the city since the demise of Pablo Escobar -- and the narco-paramilitary group known as the Urabeños. The war is fought by proxy: both sides build up a network of allied street gangs known as "combos," which fight over the "invisible borders" that divide the city into criminal territories

Displacement is part of each sides' strategy.

"It is an instrument of war," said Fernando Quijano, director of the Corporation for Peace and Social Development (Corpades) and an expert on Medellin's urban conflict. "They know what it's good for -- it's good for making more money, for taking control. It is good for ruling, for building a social base."

Territorial disputes are one of the main drivers of displacement. According to Quijano, displacement levels are usually highest around the edges of a conflict hotspot, or in between two areas controlled by warring groups. Gangs will often seize strategically located houses on the borders of their territories, which are then used as guard towers, from where approaching enemies can be spotted and repelled. Sometimes they mark boundaries or territorial advances by seizing and destroying houses.

The gangs and the mafia networks they serve also use displacement to build what Quijano calls an "obligated social base" -- a compliant population cowed by the ever present threat of having to abandon their homes.

"It's -- 'I can displace you if you don't support me,'" said Quijano. "This weighs heavy on the people -- you are with me or against me. If you are with me then hide this rifle. If you're with me then one of your sons is going to war. If you're with me then give me lunch, tell me what's going on around here."

Displacing people has also become a revenue stream for gangs, who will rent or sell abandoned houses, often to friends, family and associates in order to help repopulate the territory with their allies.

"Forced displacement is very profitable," said Quijano. "Today, we are looking at the possibility of a criminal real estate agent."

Seized houses are also put to use as lodgings for gang members, stash houses, drug sales points and, according to one community leader who spoke to InSight Crime, as places to rape and sexually abuse girls.

While displacement is a strategy with few drawbacks for gangs, the impact is devastating for the victims.

"I lost the people dearest to me, I lost lifelong friends, and I ended up alone because now I can't even go out and chat with my neighbors because they think they will be displaced next," said "Luis," a social worker who did not want to give his real name because he helps youths leave behind gang life. Luis was forced to flee his home in west Medellin after constant threats culminated in a drive-by shooting on his house.

The emotional trauma of displacement is, for many, compounded by an economic crisis as victims also have to abandon their work in the neighborhoods where they live and, if they register as victims, survive off temporary state aid.

The financial aid victims can get rent for up to six months, but this is often not enough time to get reestablished in a new neighborhood or for conditions to change to allow them to return to their homes.

"Being displaced -- aside from the problem of leaving your roots, your home, your family, and your friends -- it is also a problem because the state itself throws you into poverty," said "Diego," another who was forced to leave his home because of his community work, and did not want to give his real name.

For many victims, the dynamics of Medellin's conflict and the communication networks established by the Oficina and the Urabeños mean there is simply no place to turn.

"You leave a neighborhood controlled by the Oficina and you go to a neighborhood where the so-called Urabeños are," said Quijano. "What do the so-called Urabeños think when they see you? That you come from an enemy zone, and they throw you out. Where can you go? To an Oficina neighborhood."

The result, says Quijano, is a population of "nomad victims."

Those who do stay in a neighborhood controlled by the enemies of the gang that displaced them can often find themselves dragged into the same conflict that drove them out in the first place.

"Because you have come from [where their enemies are], they are going to ask you to inform on them -- how they work, who they are, where they live, how you can help attack them," said Diego.

However, despite the often intractable problems facing those who choose to flee in the face of gang threats, few withstand an order to leave.

"Those that stay, die, or they disappear and we never hear of them again," said Diego.

A City Divided

Although recorded levels of displacement have hit unprecedented highs in the last few years, intra-urban displacement is not new to Medellin, or to Colombia. It has been a feature of Colombia's conflict in urban areas and in recent years has reached crisis levels in Medellin and other violence-racked cities such as Buenaventura and Cali.

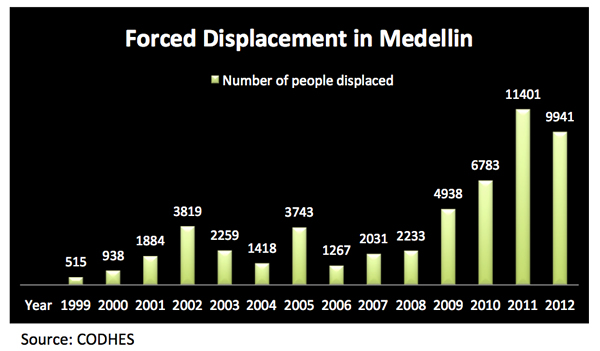

The first dramatic peak in the Medellin displacement figures collated by the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (CODHES) [see graph below] came in 2002, which saw 3,819 recorded victims -- up from 1,884 the year before and 938 in 2000. The leap coincided with Operation Orion, a military invasion of the Comuna 13 district in the west of the city, which seized control of the area from guerrilla forces and turned it over to the paramilitaries of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC).

However, it was in 2008 when the number of recorded forced displacements began to accelerate at a startling rate. The year marked an epochal shift in the Medellin underworld after Diego Fernando Murillo, alias "Don Berna," was extradited to the United States. Don Berna was head of the Oficina de Envigado, and commander of the city's paramilitary forces and his departure spaked a war of succession that split the Oficina into two warring factions: one led by Erick Vargas Cardenas, alias "Sebastian," the other by Maximiliano Bonilla, alias "Valenciano."

With the city territorially divided into areas controlled by gangs loyal to one side or the other, displacement more than doubled in the first year, rising from 2,233 victims to 4,938, according to CODHES' figures. By 2011, it had reached 11,401 victims. Although Sebastian and Valenciano are now both behind bars, the war they unleashed continues in the guise of the battle between the Urabeños and the remnants of the Oficina.

Despite the shocking statistics and its brutal impact, intra-urban displacement remained a hidden crisis for many years.

"Displacement, like recruitment of minors, are two criminal activities that unfortunately have not been made visible by the authorities and have not been legally punished," said Jorge Mejia Martinez, Medellin's Secretary for Governance and Human Rights.

It is only since last year that the Medellin Mayor's office has dedicated serious efforts and resources towards addressing the problem. But it is a slow process, Mejia said.

"It has been a learning process, but one in which we have progressed," he said.

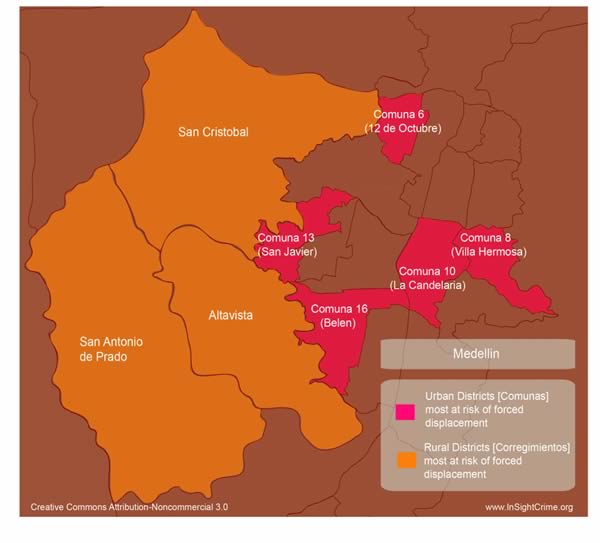

In that time, the authorities have been looking to react quicker to displacement, both before and after it takes place. Their aim is to become a preventative force by deploying specialized mobile units to the most at-risk parts of the city to detect and halt displacement before it takes place.

In the long term, Mejia believes two things are needed to stem the tide of displacement: the presence of the security forces and the presence of public investment. The secretary cited the recent mass displacement in La Loma, a neighborhood in Medellin's troubled Comuna 13 district, as an example of how the authorities want to operate.

In La Loma, 355 people from 96 families were given 48 hours to leave their homes, an order they obeyed despite the deployment of both the police and the army. However, the mayor's special Victims Unit quickly stepped in, first by sealing off the houses, then accompanying victims on every step of the return, establishing a near constant presence in the neighborhood. As a result, the majority of the families are now back in their homes.

Mayor Anibal Gaviria held a security council meeting in one of the abandoned houses, in which he announced the deployment of a mobile police unit to the neighbourhood. Security was further reinforced with a new army control point in the area.

Police and prosecutors then arrested 16 people -- among them one of the neighborhood policemen -- in a 300-person strong raid, and said the gang behind the displacement was dismantled.

While Gaviria has been keen to talk up the case of La Loma as a symbol of his administration's progress in tackling displacement, others remain more skeptical.

"The problem in La Loma is going to get worse. Now they have made those arrests, what is going to happen in the sector that the gang had occupied?" said Diego. "The group that was there before them, which has family and roots there, is going to retake the sector."

Diego is also critical of the administration's motives in dedicating so much attention and resources to La Loma.

"It's all a question of it being made public by the media, and human rights defenders," he said. "That's what moved the administrative apparatus. If it hadn't been for that, it would have gone down like in many other places -- badly."

However, both victims and the authorities agree on one thing -- that the biggest challenge they confront is reaching people too scared to officially report their displacement. These hidden victims are the reason why no one believes the official displacement figures. They are also a potent symbol of the breakdown in trust between the state and the communities under siege.

The reason people do not report their displacement, said Diego, is that while it may take months to carry out an investigation into the gang members responsible, it takes just hours for the gangs to find out who is talking about their activities.

"When you publicize a situation, the criminals know," he said. "And the police don't turn up, or they look at you like an enemy."

It is an issue Jorge Mejia readily acknowledges.

"These types of problems discourage reporting the crime. And it is true that there are members of the security forces, and members of the prosecutor's office that are close to organized crime in Medellin," he said. "But you have to say to the people: 'If you don't report it, the actions of the authorities will be very limited and we'll stay in the hands of the criminals.'"

However, in Medellin's conflict zones, the criminals, not the state, are the authorities.

"They become the state; complaints, claims, problem solving, needs, requests -- first they go to these people, not the state," said Diego. "So it is an issue of living alongside them, and trying to survive within the way of life they have imposed on the community."

Living under such mini-tyrannies, the calls to trust the state authorities ring hollow, even though victims know if they stay silent, they stay hidden.

"It is like a vicious circle, and there are very few ways out," said Diego.

The names of victims interviewed for this article have been changed to protect their identities.