Although the El Salvador gang truce has significantly lowered the country's homicide rate, the distribution of violence has remained nearly the same, raising questions about how wide the effects of the truce have actually been.

It is undeniable that the gang truce between El Salvador's two biggest gangs -- the MS-13 and the Barrio 18 -- produced a drastic fall in homicides at a national level, from a rate of 72 homicides per 100,000 residents in 2011 to 32 per 100,000 in 2012. Nonetheless, a more detailed analysis of lethal violence, using statistics from the National Police, shows the following:

i) The decrease in homicides did not occur in all municipalities -- in 20 percent of the 262 municipalities it had no effect.

ii) Gradually, as time has passed, the number of municipalities in which homicides are increasing has risen.

iii) In the same way that homicides rapidly decreased, a new spiral of violence could abruptly begin. Alerts have been raised about a process of escalation that, if not contained, could take the country back to levels of violence similar to those seen prior to the truce.

This two-part series will analyze the spatial dynamics of homicides in regard to the truce, with the objective of identifying factors that are key to preventing a new escalation of violence. This exploratory, unfinished analysis aims to study the truce's gains using available information -- with all of its deficiencies. The objective is to start a discussion that reaches beyond politically and ideologically charged debate, and examine the truce via empirical evidence. It is precisely this evidence that should be used to guide public security policy.

Where the Truce Has Not Been Evidenced

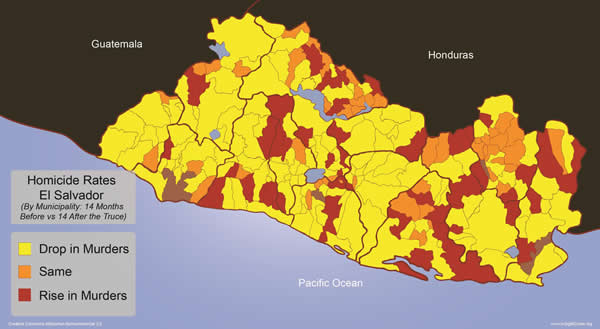

Comparing the 14 months prior to the truce (January 2011 to February 2012) with the 14 months following the implementation of the truce (March 2012 to April 2013), we can see that in 58 percent of municipalities (153 municipalities) the number of homicides dropped. In 20 percent of municipalities (52 municipalities) there was no change, and in the other 22 percent (57 municipalities), lethal violence increasd. A key element of the truce is that it has achieved a notable decrease in homicides in 24 of the 25 municipalities in which over 50 percent of the country's total homicides were concentrated -- within this grouping of municipalities, homicides increased only in San Pedro Masahuat. This is one key factor to emphasize: the impact of the truce in a country where violence manifests itself most intensely in a limited number of municipalities.

Using a map to determine the geographic behavior of homicides after the implementation of the truce, we can find patterns of continuity in the 57 municipalities in which lethal violence increased. As the map below illustrates, the municipalities where the pacifying effects of the truce have not been evidenced form part of a series of trafficking corridors, extending from Honduras to the Pacific Coast and El Salvador. This distribution of homicides should catch the attention of any uninformed observer looking for explanations as to why the greatest number of homicides takes place in these areas.

Nevertheless, coming up with a hypothesis as to why murders are concentrated in these regions is not easy, especially given the complexity of the gangs, composed of hundreds of cliques distributed throughout El Salvador; the existence of other criminal groups (drug traffickers and independent criminal organizations); and the existing gaps of information on conflict and violence dynamics in these territories. The first analysis that is needed is to contrast this map with the presence of the maras -- a task that exceeds the objectives of this article.

Nonetheless, the spatial analysis of homicides in various cities and countries throughout Latin America has allowed us to identify so-called contagion dynamics -- or the diffusion of violence. These dynamics are usually linked to one or more of the following factors: 1) the struggle between groups; 2) the process by which criminal structures expand; 3) the violent settling of debts between criminal organizations; and 4) the formation of trafficking corridors for illegal goods.

Given the dynamics of violence and crime in El Salvador, it is imposible to dismiss any of these alternatives as a possible explanation of why the truce has not worked in some parts of the country. It should also be kept in mind that, as noted by Jose Miguel Cruz, a professor at Florida International University, the gangs can only comply with the terms of the truce by recurring to the same mechanisms that the truce is trying to eradicate; that is to say, the use of severe violence. To be more clear: the truce needs violence in order to function.

The sharp drop in homicides shows that, effectively, the maras are key producers of El Salvador's deadly violence. At the same time, the persistent levels of violence raise questions about the actors that continue producing and reproducing this violence. Even with the truce in place, it's worth remembering that El Salvador has a homicide rate (32 per 100,000) that is triple that which the World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes as epidemic violence and is above the Latin American average.

In this regard, it is interesting to note that in the year since the truce was implemented, the percentage of deaths attributed to gangs have significantly increased from 11.26 percent in 2010 to 31.1 percent in 2012, according to national police statistics and Jeanette Aguilar, the Director of the research institute known by its acronym IUDOP at the Central American University (UCA) in San Salvador.

Even so, gang homicides represent only one third of the total number of violent deaths. So who is producing the remaining 69 percent of the violence? Or have the dimensions of mara-produced violence been underestimated? Other threats ranging from intra-family violence to organized crime are likely part of the answer.

During the truce, the monthly average of municipalities experiencing homicides fell by nearly half, from 62 (January 2011 to February 2012) to 38, and has remained relatively stable. However, the level of dispersion of violence has stayed the same: while in the 14 months prior to the truce, homicides were reported in 135 municipalities, in the 14 months following the truce, this number was 129 municipalities (49 percent of the homicides in El Salvador).

In other words, in terms of geographical distribution of violence, despite the fact that the monthly number of municipalities with homicides decreased, the diffusion of violence continues to be around the same level.

The Breakdown of the Truce?

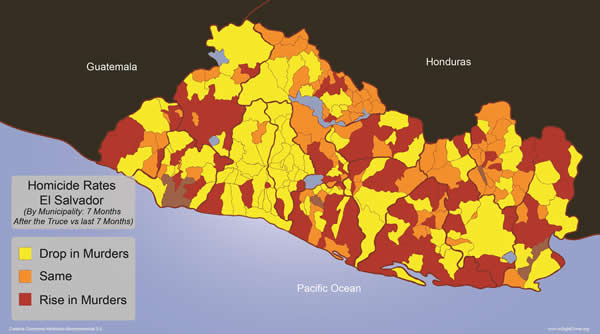

When comparing the first seven months of the truce (March through September 2012) with the second seven months (October 2012 through April 2013), using the data available at the municipal level, the geographical trends in terms of homicide reduction change. In 30 percent of the municipalities, lethal homicides increased. As can be seen in the map above, the number of municipalities in which violent deaths have risen -- comparing these two, seven-month time periods -- now covers a larger part of El Salvador, especially in the west.

However, the total number of homicides has slightly decreased, from 1,243 in the first seven months of the truce to 1,210 in the second seven months. In other words: over the course of the truce, the reduction in homicides has been sustained, but the number of municipalities in which homicides have occurred has been rising.

So while it is true that homicides rose in the months of May and June 2013 compared to the same period in 2012 -- as can be seen in the adjacent chart -- those numbers are really close to the average for homicides registered throughout the truce. What's more, the period between January and March 2013, had an even sharper increase in homicides than that which has occurred in recent months. Ironically, during that time period, few officials raised the alarm about a breakdown in the truce.

Based on these numbers, there is nothing to confirm that the truce is breaking down. However, this calculation does not take into account the recent discovery of mass graves by authorities. These bodies had been reported as disappeared since the start of the truce; the maras are the top suspects.

This is the first in a two-part installment examining the geographical distribution of homicides before and after El Salvador's gang truce.

* Juan Carlos Garzon is a visiting expert at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. He is the author of Mafia & Co.: The Criminal Networks in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia. Follow him on Twitter at @JCGarzonVergara.