A new UN report finds that organized crime bears a complex relationship to rising insecurity and violence in Latin America, which is influenced by a host of other factors, a conclusion with important implications for security policy.

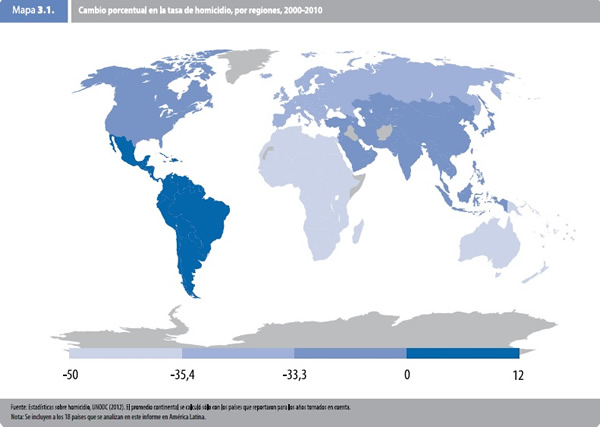

The development paper "Citizen Security with a Human Face: Evidence and Proposals for Latin America," (see Spanish pdf and English executive summary) by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) explores the various factors that explain why Latin America was the only region in the world with rising homicide rates between 2000 and 2010. The report looks at six threats impacting human development in the region: street crime, organized crime, violence against and by youth, gender-based violence, corruption and illegal violence by state actors.

Although Latin American economies have grown by 4.2 percent on average in the past 10 years and unemployment has declined to 6.4 percent region wide, murder rates grew by 11 percent, and in 11 of 18 countries surveyed, remained over the 10 per 100,000 residents considered "epidemic" levels by the World Health Organization (WHO). Rates rose particularly sharply in Honduras from 2005 to 2011, Mexico from 2007 to 2010, and Panama from 2006 to 2009, but stabilized and dropped slightly in Colombia and Guatemala. Young males are disproportionately the perpetrators of, and victims of, violent crime, with men aged 20 to 24 representing approximately 20 percent of total homicide victims in the region between 1996 and 2009.

There were 18,423 reported kidnapping cases in 14 countries in the region between 2009 and 2011, or nearly 17 a day, with the highest number occurring in Mexico, Ecuador, Venezuela and Argentina, with many so-called "express kidnappings." In regard to extortion, eight of every 1,000 Latin Americans claim to have been victims of the crime, and 20 of every 1,000 in Mexico, El Salvador and Peru. The report also found that these were two of the region's most underreported crimes.

Growing insecurity is also reflected in citizen perceptions. In 11 of the 18 countries studied in the report, over 50 percent of citizens surveyed feel insecure walking alone at night, 30 percent of Latin Americans feel unsafe in their neighborhood, and 50 percent think security has deteriorated in their country. Common crime is the main concern for residents in many countries. In one survey, more people responded that "regular criminals" were a bigger threat to their safety than either organized crime or gangs in all but four countries -- Brazil, Mexico, Honduras and El Salvador. In Argentina, Uruguay and Venezuela, over 60 percent of respondents thought ordinary crime was the biggest problem.

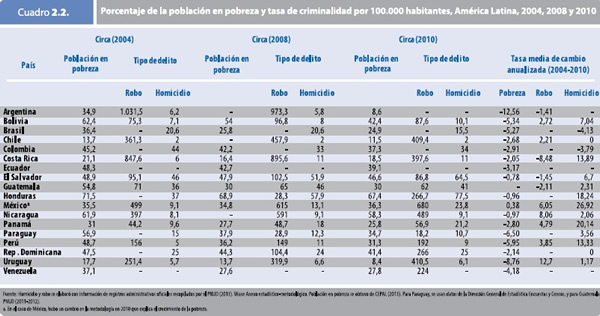

The report shows that national poverty rates and violent crime do not necessarily have a clear relationship. While Honduras was both the country with the highest poverty rate in 2010 (67.4 percent) and the highest homicide rate (77.5 per 100,000), Nicaragua, with the second highest poverty rate (58.3 percent), had one of the lower homicide rates (9.1 per 100,000). Inequality, similarly, fails to adequately explain violence and crime: Costa Rica and Paraguay had the same Gini Coefficient -- which measures income distribution -- but the former had a much higher robbery rate in 2009, at 990 per 100,000, compared to Paraguay's 18 per 100,000.

The study identifies certain socio-economic factors that likely impact crime rates. These include job quality -- many inmates surveyed said they were working at the time of committing the crime, indicating that their income was not enough to live comfortably on -- and level of schooling -- many prisoners interviewed did not complete high school. Urban growth is another likely structural cause of violence, with the majority of violent crime concentrated in cities. Though the proportion of urban dwellers living in slums decreased over the past 20 years, the absolute number rose from 106 million to 111 million.

Facilitators of crime identified included the existence of institutional weaknesses such as corruption and impunity, drug trafficking, and the availability of firearms. Between a third and half of all robberies were committed using a firearm, and the percentage was much higher for homicides, standing at 91 percent in Ecuador, 84 percent in Guatemala and 83 percent in Honduras in 2010, according to Organization of American States figures.

InSight Crime Analysis

As concluded by the study, no single factor can explain the persistently high rates of violent crime in Latin America compared to other regions of the world, and it is the "interaction of organized crime with other threats that is behind the spiraling violence and exponential growth in homicides in some countries." The question is: what is the role that organized crime plays in causing and perpetuating crime in the region?

In some countries, spikes and drops in violence have coincided with major changes in the organized crime landscape. Honduras, the most violent country, has seen rising homicides since 2005, but the sharpest spike came after the 2009 ousting of former President Manuel Zelaya and a subsequent rise in cocaine trafficking through the country. In Mexico, pushback against the dominant criminal organizations under the administration of former President Felipe Calderon in 2006 sparked a destabilizing drug war. Other situations that can break existing equilibrium include the emergence of new and particularly violent groups, such as the Zetas.

In Colombia, slightly declining homicide rates coincided with the demobilization of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), and an easing of the country’s decades-long violent conflict, though violence shifted to the cities. A sharp drop in El Salvador's homicide rate in 2012 followed the implementation of a truce between the country's two main street gangs, although this drop has not been sustained in the longer term.

There are also certain forms of organized crime that are inherently more violent than others, as Eric L. Olson, the associate director of the Latin American Program at the Wilson Center, told InSight Crime. Micro-trafficking and extortion are more likely to cause turf wars between groups at a local level than transnational drug trafficking run by bigger organizations. This is seen in Honduras and El Salvador, where extortion by street gangs is a major driver of violence. The type of criminal organization existing in an area is also important, as those that attempt to gain social and territorial control -- such as the Zetas -- are necessarily more violent than those involved only in moving product. In many cases, it is also "common criminals" who are blamed for activities like micro-extortion, though the line between the two is often not clear-cut.

Even when organized crime is not a direct driver of violence, it may have an indirect effect by corrupting state institutions and thus reducing citizen access to adequate security and justice mechanisms. Tellingly, the majority of survey respondents in countries like Peru and Bolivia perceive the police as being involved in organized crime. Though neither country has a particularly high homicide rate, both have a growing role in the regional drug trade, and Bolivia's homicide rate is rising. Olson also noted that income inequality, a factor he pointed to as an important destabilizer in the region, often affects people's access to legal recourse for crimes.

On the flip side, the growth of organized crime can also be facilitated by some of the same factors that help drive common crime -- income inequality, poverty and lack of education. The complexity of the relationship between social factors, facilitators -- such as access to guns and corruption -- as well as violence, makes it difficult to evaluate the causative relationship of these factors with organized crime. What is clear is that it is necessary to examine country-specific and local factors to better understand the nature of the problem and possible solutions.

The UNDP highlights this, stating: "the linking of various threats at the local level is what allows us to understand the high levels of crime and violence that have been reached in the region." As the report shows, and as InSight Crime has reported, moderate homicide rates in places like Mexico and Brazil mask the disproportionately high levels of violence in certain specific areas. The causes of violence are also distinct in the two countries -- while many of Mexico's most violent states are those most affected by the drug war, one study shows that socio-economic factors are more important in explaining violence in Brazil.

The report points to the need for differentiated and integrated strategies to address crime, that take into account the various social, economic, demographic and criminal contexts of each place. It notes the integral role of local government in this regard, as well as the differing strategies necessitated by common crime and organized crime -- while the former may involve strategically placed patrols, the latter requires intelligence operations. Finally, the report stresses the importance of investing in youth job training and education, strengthening institutions, careful state intervention and regional cooperation, along with security efforts, to tackle violence.