In an examination of Peru's drug flights, IDL Reporteros Director Gustavo Gorriti takes an in-depth look at how trafficking by air is organized, how lacking resources hamper authorities' efforts to combat the phenomenon and how regional cooperation is helping to fill the technology gap.

Where can you see unidentified flying objects? That depends. If you are looking for the ones that supposedly took off from Ganymede, the place is (or rather, was) Peru's Chilca desert. Good luck.

But if you are not hoping for anything more than to see unidentified flying planes that come, rather modestly, from Bolivia, the results will not be esoteric, but they are guaranteed. Neither in Pichis Palcazu nor in the Apurimac, Ene and Mantaro River Valleys (VRAEM) can you miss it. You will hear them flying and you will see them flying, the lords of the sky, sometimes alone but more often in pairs and even in fleets of four or five planes.

If the observer is in possession of a radio scanner, he or she can enrich this experience by listening to the conversations of the pilots, who speak with an unmistakable Bolivian accent, to the people who are waiting for them below. Where do I land? Here, or in the next one? Are there "ventiladores" ("fans" - code for security force helicopters) nearby?

The VRAEM and Pichis Palcazu are now among the most intensely trafficked air corridors in Peru. The difference with other regions is that in both of these, virtually all of the flights are illegal and all have the objective of carrying coca paste (300 kilos per flight) to processing laboratories in Bolivia where, without losing any of this weight, it will be converted into cocaine hydrochloride.

The frequency of the flights has increased in intensity since last year, when some police intelligence reports registered around 30 flights flying over barracks or police precincts over five or six days, in just one part of the VRAEM. Now, they calculate that there are between three and six flights daily in just the Valley, and slightly less in Pichis Palcazu.

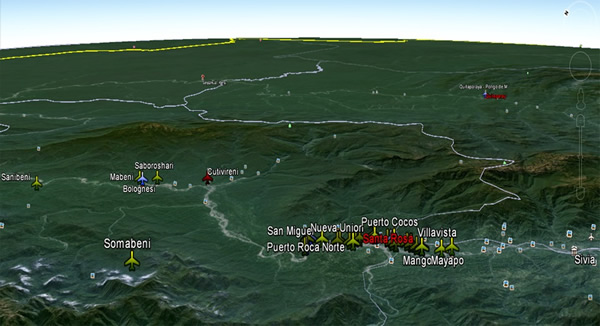

The increase in flights, which in a few months has significantly changed the form in which drug trafficking operates in the region, has been possible for a paradoxical reason: the VRAEM, the region with the highest concentration of security force operatives in the country (police and armed forces), has a totally unprotected air space. The pilots, who are almost always Bolivian, have nothing to fear as long as they are in the air. They can fly over, and they do fly over, barracks, precincts, posts and bases, before undertaking the only uncertain and dangerous part of their journey: landing on one of the various closely positioned runways (most of which are not far from the military bases - see IDL Reporteros map). These are chosen at the last moment by the group waiting for them below, in order to prevent ambushes on land and to load the 300 kilos of drugs with which the plane will return to Bolivia as quickly as possible.

How can doves be hunted without hawks, shotguns, or even slingshots? By trapping them when they are on the ground. For Peru's anti-drug police, an impotent bystander in the face of the untouchable drug flights, the only way to hunt them has been in the few vulnerable moments when the planes descend, taxi, open their doors while the land-based drug traffickers approach with their load and stack it neatly in the plane before the pilot closes the cabin, head toward the end of runway, pick up speed, and take off on the return flight.

Those are the most dangerous moments for the drug traffickers. They end disastrously when the narcos suddenly hear the shouts and gunshots that announce a police ambush, and the police contingent that managed to hide in the thicket and awaited the right moment to act emerges. When that happens, the possibilities of escape for the narcos are next to none. Nonetheless, sometimes they try, and fail.

For this reason, the local drug traffickers try to be unpredictable and to carefully examine the areas surrounding the landing strips and the access roads. In addition, they frequently receive information from locals, who benefit from their presence.

For the police, this makes it very difficult to plan, organize and execute a successful ambush of the drug planes. Nonetheless, they have managed to do it on various occasions.

There is another way to capture drug planes: when they land badly, or on a badly prepared clandestine airstrip, they crash, and the plane cannot take off again. Sometimes they burn, and sometimes, when the damage is reparable, they are hidden, but on other occasions the police seize them.

How worthwhile is nabbing four or five luckless planes among hundreds of successful flights? Very worthwhile, to tell the truth. For the anti-drug police, especially the intelligence units, each plane captured is an information treasure trove, a fascinating tale that allows them to discover how the drug traffickers operate, who they are and what their methods are.

The Old Man Who Couldn't Flee

Slightly before 12:45 on December 11 last year, the plane CP-2683 landed on a clandestine runway situated in the Codo del Pozuzo jungle. Minutes later, among threatening shouts and gunshots, the whirlwind police ambush unfurled.

The pilot did not try to take off, as his reckless Bolivian comrades -- for whom being a pilot is frequently associated with accidents and fatality -- perhaps would have.

This one had sufficient experience to know that, whatever he did, the game was over.

The 63-year-old Brazilian pilot, Carlos Alberto Paschoalin, had various years of experience, the majority of them dedicated to drug trafficking. Nearly all of his flights had been successful, but there had been occasions in which this was not the case, and the documentation of these failures left an interesting stamp on an uncommon biography.

Fifteen years earlier, on October 25, 1999, Paschoalin was captured by the Brazilian police in another landing area, at the Valle de Gorgulho ranch in the state of Para, while he was piloting a twin-engine plane (PT-VKJ) with 849 kilos of cocaine on board.

Although he was included in a federal process in Para (N° 99390113678), all evidence indicates that he did not spend much time in prison, because he was sentenced, as a free man, on July 11 last year to three years in prison -- a sentence which was immediately appealed.

Thus, in liberty, the old pilot decided to make one more flight, to the Codo del Pozuzo. Each flight represents, according to police information, a payment of $25,000 for the pilot that successfully completes the mission of exporting the drugs.

For Paschoalin, now being held in Piedras Gordas, the Pozuzo flight could have easily been his last job as a narco-pilot. Although he is a veteran of many drug transport flights, it is most likely that Paschoalin will not write about his memories, which would be fascinating, while jailed in Piedras Gordas, but rather, will quietly grow old inside the prison. In certain lines of work, silence is considered the best form of expression.

Spanglish or Portuñol?

For the special intelligence units of the Peruvian anti-drug police, the resurgence of the narco-flights created new operational and investigative challenges.

Throughout nearly the entire history of the so-called "war on drugs," the path of drug trafficking pointed from south to north -- from the jungles of the Upper Huallaga Valley and from Chapare, in Bolivia, to the cities of the United States.

Anti-drug cooperation primarily involved agreements with the US government. It was -- and continues to be -- a cooperation that is highly subsidized by the "gringos," which signifies receiving the means (from helicopters to money for investigations and the use of electronic intelligence equipment) in exchange for ceding control over investigations and a degree of sovereignty in managing and carrying out operations.

The police that worked, and continue to work, in joint operations with US forces, for example, are all polygraphed by officials from that country. The United States controls the use of the helicopters they provide to Peruvian police. The anti-drug bases, also subsidized by the gringos, have employees who audit the use of the helicopters based on what has been established in the contracts. In the majority of cases, the preferred use of the helicopters is for the eradication of coca plantations and not for other types of interventions, although they can also have a direct importance in anti-drug operations.

It is a clearly dependent relationship that involves an uncomfortable degree of subordination (from what I know, it has not occurred to anyone to suggest a Brazilian style agreement here), but which undoubtedly has certain advantages. The polygraph has served, despite the abuses and shortcomings, to maintain the operative units relatively free of corruption. The electronic intelligence apparatuses, such as legal phone wiretaps, have been greatly useful in investigative work both against drug trafficking and against the Shining Path guerrillas.

But the new air bridge does not, according to anti-drug sources, fall into the gringos' sphere of interest. The main reason is that the flights are not headed north, but rather, south, to Bolivia, and then to Brazil.

The anti-drug police units who took up the fight against this new and very threatening phenomenon were primarily intelligence agents. Without being able to count on the support the United States could have provided, they had to look for other kinds of international police cooperation in a battle they cannot undertake alone.

It helped them that, for at least the past few years, cooperation between the DIRANDRO (the anti-drug police) and the Brazilian national police had markedly increased.

Trained under the same model as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Brazilian federal police developed a rapidly growing cooperative relationship with the DIRANDRO, in much more horizontal terms -- more "south-south" -- than that with the United States. It also meant less technology and resources, though not less ambitions.

The DIRANDRO's special intelligence units also established collaborative contact with their Bolivian anti-drug counterparts, the FELCN. And, facing a lack of latest generation technology, they looked to apply the classic art of a good investigation in this tripartite alliance: obtain, analyze and process the pertinent information in the most accurate and opportune manner possible.

Clues, traces, and personal information helped them answer questions such as: what is the history of the drug trafficking planes and their pilots?

For most police, this was and still is a question without an answer. Day after day they see the planes flying high in the sky over the VRAEM and Pichis Palcazu. Sometimes, they take a snapshot with a cell phone camera from their barracks or a military or police base, when the flights come very close. But they arrive and depart from what seems to be an information gray area that they have not managed to crack open.

But the DIRANDRO investigators managed to get some clear and valuable information from inside that haze.

For example, the airplane CP-2782 told a story that was as eloquent as it was silent.

On October 18 last year, CP-2782 was found in a clandestine landing area. It was parked in the middle of the runway, covered by leaves and weeds in a somewhat clumsy attempt to camouflage it, and its rear undercarriage was torn.

The plane was a Cessna model C-206. It had been purchased some months earlier, that past February, in Miami, and was flown from there to Bolivia via Manaus, in Brazil.

That city is one of the mandatory stopover points for planes headed to Bolivia. There have been around 900 planes that have reached Bolivia from the United States -- the majority via Manaus. No less than that.

In Bolivia, the airplane was registered with the plates CP-2782. Its flights within that country were legal.

Its final trip, which would end in an accident on the clandestine landing strip in Ayacucho, began legally, with an official flight plan to Bolivia. As a destination, the plan had marked the Maravilla airport in the Beni province. That airport had also been declared a destination point for other flights that ended up in Peru.

Airplane Number CP-1800

On November 24 last year, the Bolivian plane CP-1800 landed on a clandestine airstrip in Pichis Palcazu, where it was awaited by a hidden contingent of special operations police. There was no surrender, but rather, a shootout in which the pilot, Angel Roca, was gravely injured, and died shortly thereafter. Along with him, police captured two other people and seized various firearms, satellite phones, VHF radios and two GPS systems. And 300 kilos of cocaine, which had apparently already been stowed away and was ready for takeoff.

Angel Roca, the pilot who was killed, had a long criminal record. His first registered arrest took place in August 1993, in a joint operation between the Bolivian rural patrol unit UMOPAR and the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which at the time had a strong presence in Bolivia. A total of 18 people were detained -- two Colombians and 16 Bolivians. Among these was Roca, who was in charge of the aerial transport of the drugs.

Years later, in 2001, Roca was arrested in the state of Goiais in Brazil, and accused by the federal justice system of international cocaine trafficking and illegal arms possession. By 2013, however, he had regained his freedom, and was again involved in the aerial transport of cocaine. With this goal, he headed towards his destination, which turned out to be his final destination: the Peruvian jungle.

Airplane Number CP-1959

The history of this plane was reconstructed based on the remains from a fire, seen for the first time from a helicopter flying over Pampa Hermosa, Puerto Inca, in Huanuco, on November 26 last year.

The plane had been burned after, according to locals, an attempted landing ended in an irreparable accident. Not much remained, except for a piece of the tail with the Bolivian flag painted on it, and a scorched identification tag from the plane's manufacturer, where the serial number could be made out.

Using this information, the FELCN in Bolivia was able to provide the registration information of the plane and its owner.

It was the Cessna CP-1959, whose owner, Carlos Botero Barbery, had a police and court record for drug trafficking. He had been detained in December 2010 with cocaine and precursor chemicals. Apparently, he was back out of custody at the time his drug plane crashed on the clandestine landing strip in Huanuco.

The Capture of the CP-1847

If the narco-pilots choose their landing point at the very end of the journey, after coordinating with the group on the ground, which is carrying the drugs and is in charge of security, how do the police manage to ambush the planes?

With good intelligence. The landing strips have to be located close together, so that the groups on the ground can easily move from one to the other, without the plane having to spend much time on the ground.

This is what happened with the group of police that, on March 29, captured the Bolivian airplane CP-1847 near the town of Santa Rosa. The plane was carrying 300 kilos of cocaine and was protected by an armed security contingent at the time the police operation was carried out.

That time, the operation was a joint action by the DIRANDRO's special operations division in the VRAEM, reinforced by the tactical actions group of the same force, the not very euphonic but effective GOATJ.

The contingent responsible for the operation was very small, in order to be able to successfully infiltrate the area with little risk of detection. The infiltration began, according to well-informed sources, on the night of March 26. During the following three days, the group concealed itself in the areas surrounding the landing strip that they believed would be used by the drug traffickers.

At 10am on the 29th, the Bolivian airplane landed. As they came nearer, the operatives, without being discovered, saw a group of 10 people loading the plane with drugs. The intervention group sprang into action, and became engaged in a shootout with the men in charge of security for the flight.

Minutes later, the situation was brought under control. Near the airplane, they found Ezequiel Guinea, who had been hit in the knee. In the plane was the Peruvian national Hugo Quiroz, and another person who was mortally wounded, the Bolivian national Julio Jimenez, who died shortly thereafter.

In and around the plane, there were a number of bags of cocaine that brought the total to more than the 300 kilos of drugs that would have made up the complete load.

After another short round of shooting, another helicopter arrived with reinforcements from the VRAEM Special Command. This allowed them to effectively secure the area and finish their legal tasks.

What Is the Business?

Why do the VRAEM narco-traffickers export washed coca paste to Bolivia, when in the recent past they had developed simplified methods to produce cocaine hydrochloride in the VRAEM itself?

According to police intelligence sources, one of the reasons is the quality of the final product: in the VRAEM they use acetone to make the cocaine hydrochloride, while in Bolivia they commonly use ether for the same process. Moreover, the variety, price and quality of the precursor chemicals available in Bolivia are advantageous for the drug traffickers.

A kilo of coca paste in the VRAEM costs $900. In Bolivia, this rises to $1500.

This difference covers the basic costs of drug exportation, and explains the earnings:

The rental cost of a clandestine airstrip fluctuates between $10,000 and $15,000 per flight.

An experienced pilot makes $25,000 per flight. At the other end of the spectrum, a novice can make as little as $10,000. Training academies for pilots have proliferated in Santa Cruz: where once there was one, now there are seven. The price of the course has also multiplied by seven.

The rental cost of the airplane for each narco-flight is around $70,000.

When the airplane is about to take off from the VRAEM, its 300 kilo load of drugs is worth $270,000.

When it lands, hours later, in Bolivia, the same load is worth $450,000.

In addition to the individual flights, authorities have registered various cases of fleets of four or five planes that approach the clandestine landing strips in the VRAEM at the same time.

One interesting case illustrates the combination of caution and recklessness with which the Bolivian narco-pilots approach their most dangerous point in the journey.

A fleet of four planes nears the landing strips designated to be used to pick up the drugs in the VRAEM. The pilots speak amongst themselves using the pseudonyms Cris, Primo, Bigote and Uri.

Cris tells Primo that he is not going to land, but rather, is turning around because the people on the ground have told him "The Law" is there.

Uri says that he is turning back as well, since they have also told him "The Law" is waiting below. The conversation continues among the four men to determine where the "ventiladores" (security force helicopters) are. When they are certain they have seen them nearby, above a river, the four men decide to go back.

But, despite the notably professional work of the anti-drug police's intelligence teams, which have successfully used the limited information from previous captures to investigate and reveal a good part of the drug trafficking organizations' structure, methods and routes, the reality is that the numbers are still overwhelmingly in favor of the drug traffickers.

Just a dozen flights have been captured on land, after being ambushed or suffering accidents. It is possible that there are various other cases of accidents that have not been reported.

Every day between three and six narco-flights reach Bolivia just from the VRAEM. This means more than 20 per week, and more than 80 per month. The number could be greater, or it could be less, but it is evident that the interdiction that occurs is minimal, meaning that the cost is more than acceptable for the drug traffickers and absolutely unacceptable for Peru.

Gustavo Gorriti is a Peruvian journalist and the current director of IDL Reporteros, where this article originally appeared. The piece was translated and reproduced with permission. See the Spanish original here.