A report by a panel of high-profile political figures states that the taboo around discussing new approaches to drug regulation has been broken. But while alternative drug policy advocates have enjoyed significant victories in the past few years, there's still room for setbacks.

The Global Commission on Drug Policy -- a 21-member panel that includes four former presidents of Latin American countries and former United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan, among others -- published a new call for drug policy reform on September 9. It was a follow-up to the Commission's 2011 report, which recommended a major paradigm shift in terms of how the United Nations and the United States have traditionally approached this issue.

Since then, Latin America and the Caribbean have seen some key advances in drug policy. The Commission names the following events as the most noteworthy:

- Uruguay became the first country in the world to establish a legal, regulated market for marijuana.

- The Organization of American States (OAS) published a report that the Commission called "the first report from a multilateral organization to meaningfully engage with wider drug law reform questions."

- Bolivia withdrew from a major UN drug convention, rejecting the classification of coca as an illicit substance (Bolivia was later readmitted, although the dispute hasn't been resolved).

- Jamaica is in the process of changing its drug possession laws and is poised to allow people to carry small amounts of marijuana for personal use.

All of this lends credence to the claim in the Commission's 2014 report that the taboo around talking about new approaches to drug regulation has now been "broken." It is no longer a question of starting the debate -- it is now a matter of taking action.

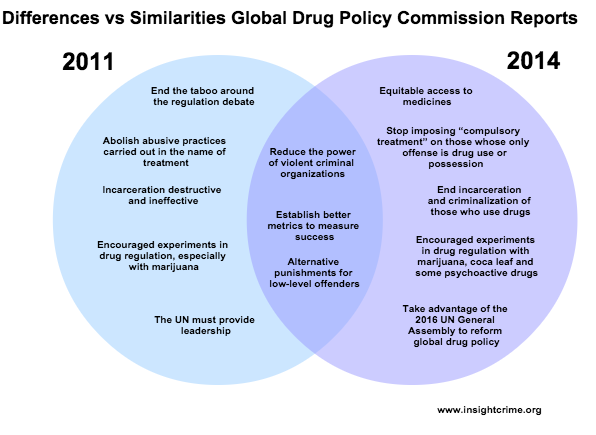

In the new report, the Commission builds and expands upon the recommendations it released three years earlier. While the 2011 report recommended that governments explore alternative punishments for those involved in low-level drug crimes, the Commission now urges that the world end the incarceration and criminalization of those found using or carrying drugs.

The new report is also more specific in condemning abusive practices related to rehabilitation: it singles out the imposition of "compulsory treatment" on low-level drug offenders as a practice that must stop.

And while the 2011 report encouraged governments to experiment with new drug regulation models for cannabis, the Commission has now expanded that recommendation to include "coca leaf and certain novel psychoactive substances."

There's still significant overlap between the two reports, as the diagram above illustrates. Both documents urge governments around the world to focus on reducing the power of large, violent criminal organizations, but do not offer more specifics. And both discuss the need for better metrics to measure what a "successful" drug policy looks like.

The latest Commission report urges that the 2016 United Nations General Assembly Special Session be used as a staging ground to lay out a new framework for approaching drug policy.

InSight Crime Analysis

As bold as the Commission's newest recommendations are, there's still a way to go before there is serious discussion in Latin America about legalizing other drugs besides marijuana. Even in a country like Uruguay -- where the production, sale, and use of marijuana is legalized -- the government takes a tougher stance on other substances. And when leaders across the region have spoken out about being "open" to debating drug policy, it's almost always been in the context of legislation on marijuana, rather than cocaine and heroin.

Even though there's little indication that governments in Latin America are prepared to experiment with legalizing drugs besides marijuana in the near future, the Commission's assertion that "the taboo has been broken" does ring true. And it may well be that by the UN General Assembly Special Session in 2016, there will be more nations ready to take historic action not just in debating drug policy reform, but actually doing something about it.

Between now and then, there are a number of ways Latin America could continue pursuing a more open drug policy, although again, these are mostly related to marijuana regulation. Mexico's Federal District, for example, may end up finally voting on a marijuana regulation proposal. Meanwhile, Caribbean trade bloc CARICOM has called a commission to review marijuana laws in the region.

It is also worth noting that if more states in the United States follow the examples of Colorado and Washington and vote to legalize the recreational or medicinal use of marijuana, this will reverberate throughout Latin America.

However, the willingness to jump on board with new policy proposals may be largely dependent on the success or failure of experiments in other countries. And in Uruguay -- the only country in the world with a legal marijuana market -- there's a looming question of whether the regulation law will survive a change in government. In one recent poll, the majority of respondents (64 percent) said they wanted the law revoked. Some have questioned the law's future should ruling coalition the Frente Amplio (Broad Front) lose an absolute majority in the general elections this October.