Colombia's military has outlined areas of focus for its future functions should peace agreements be signed with the FARC and ELN guerrilla groups, several of which involve its potentially problematic, but likely necessary, role in anti-crime efforts.

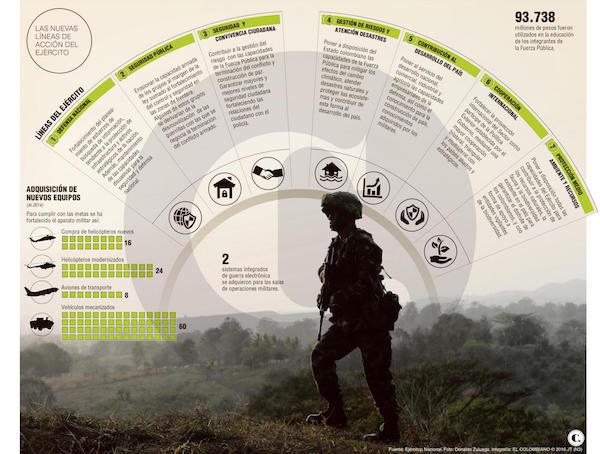

El Colombiano reported that military leaders identified the following seven areas for army operations in a post-peace agreement scenario:

- National Defense

- Public Security

- Citizen Security

- Risk Management and Disaster Response

- Contribute to National Development

- International Cooperation

- Environmental and Resource Protection

Within these seven points, El Colombiano reports that three lines of action dominate:

- Sword of Honor: A campaign to permit the army to fight against criminal threats.

- Transition to Peace: Focus on supporting the disarmament, demobilization, and reinsertion of guerrillas.

- Transformation: The creation of a Command for the Transformation of the Army, which will develop the military's strategy for change through 2030.

"Today our army is on a war footing, but at the same time it has the capacity to transform itself," El Colombiano quoted Viceminister of Defense Aníbal Fernández de Soto as saying. "Not only by modernizing, but also by transforming its culture and mindset, and supporting that with military education."

Retired General Jaime Ruiz Barrera, president of the Association for Retired Officers of the Armed Forces (Asociación de Oficiales Retirados de las Fuerzas Militares), noted that signed accords would not immediately usher in peace. He said that would take several years to achieve. Barrera said there would be a continued need for soldiers to both ensure the agreements of a peace accord are properly implemented and to confront other threats, such as Colombia's criminal bands (BACRIM, for the Spanish bandas criminales).

Political analyst and armed conflict specialist Marcela Prieto agreed, telling El Colombiano the military's considerable skills and knowledge gained during its years of fighting should not be ignored during the post-agreement period. "The Colombian army," she said, "should continue collaborating with the rest of the security forces and not just focus, as many have suggested, on guarding border regions."

The Colombian government has been in peace negotiations with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – FARC) since 2012, and recently opened formal peace talks with the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional – ELN).

InSight Crime Analysis

Having been at war for the past half-century, the Colombian military is concerned that it will lose power and purpose should peace agreements be signed with the FARC and ELN.

The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) has estimated the end of Colombia's armed conflict could result in the military's numbers being reduced by as much as 100,000 from the current level of 272,000. To prevent a security vacuum from occuring, the country's National Police (Policía Nacional de Colombia – PNC) is trying to increase its 184,000-person force by 10,000 recruits per year.

Yet, as WOLA notes, it would take years for the PNC to fill the personnel gap left by a swift cut in the armed forces.

Questions also remain over the PNC's ability to fulfill its constitutionally mandated role of providing internal security. Recent fieldwork by InSight Crime in 60 municipalities throughout Colombia found that many police in isolated regions do not patrol outside urban centers, and in some cases do not even leave the police station. That dynamic is unlikely change significantly following a peace agreement.

Doubts about the PNC's abilities have helped guide the military's search for a post-agreement mission. Military strategists have identified the fight against organized crime as an area where the armed forces can focus its resources and capabilities. And given the PNC's lack of capacity, the military stepping into such a domestic security role will likely be necessary in the immediate to near term.

The Colombian military serving a policing function, however, rightly raises concerns.

Mexico, for instance, offers some stark examples of the dangers that accompany militarization of the fight against organized crime. There, soldiers have been implicated in numerous human rights violations since former President Felipe Calderon gave them a bigger role in tackling criminal structures, including extrajudicial killings.

El Salvador's use of the military for domestic security functions has also come under scrutiny. Recently, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), a division of the Organization of American States (OAS), held a hearing on extrajudicial murders and other alleged abuses committed by police and soldiers while responding to the country's ongoing security crisis.

History shows the Colombian military is not immune to such transgressions. Indeed, one of the most emblematic and outrageous instances of widespread human rights violations in Latin America is the "false positives" scandal, in which members of the Colombian military executed civilians and passed them off as enemy combatants.

Nonetheless, not involving the Colombian military in the effort to dismantle criminal structures, or drastically cutting the number of soldiers, presents several equally grim scenarios. One is the risk of creating space for illegal armed groups to flourish in the absence of a strong police force. Another is the question of what happens to soldiers who suddenly find themselves out of a job. Having gained a unique set of skills, such as proficiency with weapons and familiarity with military tactics, soldiers make appealing recruits for criminal organizations -- as evidenced by Mexico's Zetas, whose initial cadreof members were heavily trained Mexican special forces.

Ultimately, the end goal is for police to be able to provide domestic security without military support. Until the Colombian police are up to the challenge, however, the military is likely to be given a role in the country's anti-crime efforts.