A controversy over Colombia's drug strategy reflects an official sense of urgency to reverse booming coca cultivation as the country prepares to end over 50 years of armed conflict with the FARC rebel group.

In a September 2 letter (pdf), Attorney General Néstor Humberto Martínez asked Colombia's National Council on Narcotics to consider reinstating the aerial fumigation of coca crops.

The aerial spraying of coca with the herbicide glyphosate was a pillar of Colombia's anti-narcotics strategy for years, but in May 2015 authorities banned the practice after a World Health Organization report found it could cause cancer. Spraying formally ended on October 1, 2015.

The ban on aerial fumigation put sole responsibility for forced coca eradication on manual eradicators. But Martínez cited four reasons why manual eradication “has become impossible” in the current climate:

The 345 blockades and protests registered so far this year that have prevented manual eradicators from carrying out their job.

The increase in anti-personnel mines and other weapons in eradication zones.

The dangers manual eradicators face from illegal armed groups and tropical diseases.

The decrease in the number of Mobile Eradication Groups from 900 to the current count of 200.

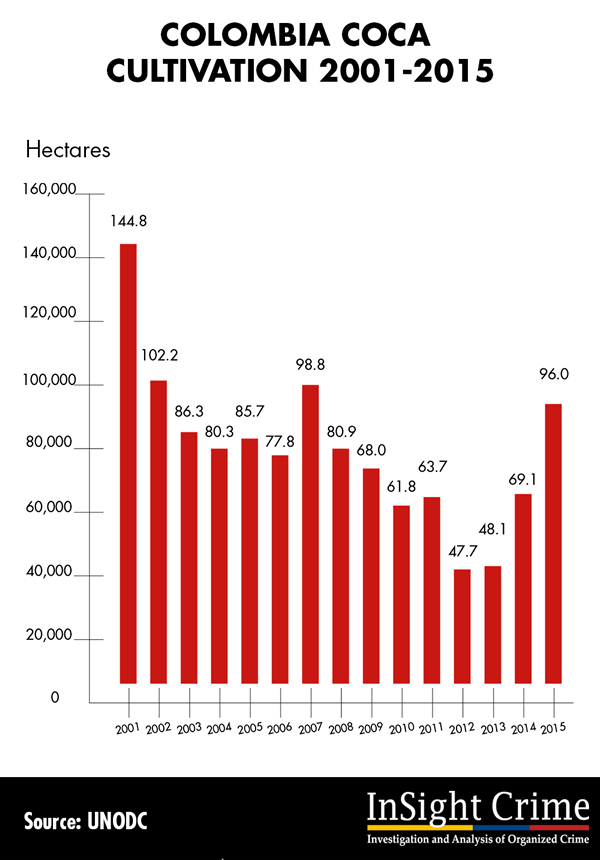

To support his position, the attorney general noted with alarm the dramatic rise in Colombia's coca cultivation. It rose 39 percent in 2015 to 96,084 hectares, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, more than double the nadir of 47,788 hectares registered in 2012.

Martínez's proposal kicked up a minor political storm. The country's Health minister, Alejandro Gaviria Uribe, was quick to repudiate the attorney general's letter, saying “the reasons for the prohibition of aerial spraying with glyphosate remain valid.” The editorial board at El Espectador, one of Colombia's most widely circulated newspapers, alsosharply criticized the proposal.

Not everyone was so unreceptive, however. Prosecutor General Alejandro Ordóñez Maldonado sided with Martínez, and placed the blame for the coca increase on the fumigation ban.

“We knew that with the suspension of the fumigations we would be swimming in coca,” Ordóñez Maldonado said.

President Juan Manuel Santos appeared to put the issue to rest, for now, by dismissing the possibility of restarting aerial fumigation during an interview with the AFP on September 5.

The proposal comes less than two weeks after Colombia's government and its largest rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia - FARC), announced a final peace deal after four years of negotiations. The two sides will sign the peace deal in late September, and the Colombian people will either approve or reject the agreement in a referendum set for October 2.

InSight Crime Analysis

The attorney general's proposal is a product of the frustration authorities feel over the explosion in coca cultivation Colombia has experienced in recent years, which has wiped out the hard-earned gains they had been building on since the mid-2000s.

The US government, an important ally to Colombia and financial backer of the massive security aid package known as “Plan Colombia,” shares this frustration.

“The government of Colombia no longer has the same eradication program that they had for the last 20 years or so,” said William Brownfield, the top US anti-drug official for the region, during congressional testimony in June 2016. “They have stopped all aerial eradication, and they have not replaced it with ground-based manual eradication.” (Listen to audio from the testimony here.)

More specifically, the timing of Martínez's proposal underscores the dangers the rise in coca present to the government's post-peace agreement plans.

“The recent dynamic of the illicit crops constitutes an effective threat to peace in the territory,” his letter states in bold font.

As the FARC prepare to exit a more than 50-year-old conflict, the race among Colombia's other illegal armed groups to take over strategic territory currently in FARC possessionhas already begun. And with the FARC controlling as much as 70 percent of all the coca grown in Colombia, there is no bigger prize than the FARC-supported coca fields that dot hillsides across the country. In Colombia, where market fluctuations have prompted a migration from illegal mining to coca, green is the new gold.

The attorney general said areas that have seen an especially large increase in coca cultivation, such as the departments of Norte de Santander, Caquetá, Nariño and Putumayo, are among the most vulnerable to fighting among illegal armed groups, which he notes "has already become apparent.”

Of course, the peace agreement provides Colombian authorities a window of opportunity to reduce coca cultivation by gaining a foothold in the remote communities where it is grown in abundance. The FARC, which is arguably the most important player in the world of cocaine production, has agreed to break its links to drug trafficking. It is even participating in a pilot crop substitution project in the department of Antioquia, the capital of Colombia's illicit drug trade.

But Colombia's government hasn't been as quick to act as its criminal groups.

“The government really isn’t implementing a strategy right now -- that’s where the problem lies,” said Adam Isacson, a senior associate for regional security policy at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA).

Isacson said the FARC peace accord foresees the government increasing its presence in coca-growing areas and integrating local farmers into the legal economy. He called this “the most effective option” for reducing coca cultivation, as well as the most expensive, but noted “the accord isn’t being implemented yet.”

Which means Colombia has essentially ended up in the worst of both worlds: it ended aerial fumigation almost a year ago, but has yet to replace it with a viable alternative.

“Rather than reinstate fumigation, Colombia needs to pursue the options it says it plans to pursue, to get these plans off the table and put them into practice,” Isacson told InSight Crime.

The longer the Colombian government waits, the more time criminal groups will have to fill the vacuum left by a departing FARC; and the more territory these groups claim, the more difficult it will be for the government to turn back the rising tide of coca. Time is of the essence.