In October, the Mexican Navy killed the Zetas' top leader, Heriberto Lazcano, alias "Z-3." Lazcano was a mythic figure, evident in the way the group marshalled several fighters to steal his body from the morgue following his death.

Lazcano was also perhaps the only thing standing in front of the complete fragmentation of this powerful organization. Indeed, the Zetas have been splitting at the seams since at least the middle of 2012. Various commanders have declared war on each other, and the new top commander, Miguel Treviño, alias "Z-40," is scrambling to keep the organization intact.

It will not be easy. Even before Lazcano's death, the Zetas were taking severe hits, especially in Monterrey. January 16, 2012, was a typical day in the battle for Monterrey. At 4 p.m., men armed with AK-47s got out of a taxi in a north Monterrey neighborhood and executed a young couple at the woman’s residence. The female victim was identified as Karla Zuniga Luna, 25. The male was simply referred to as “El Piolin.” The police told the media that the residence was a drug distribution point.

That same day, Ricardo Flores Rodriguez was assassinated by men carrying AK-47s as he walked down the street in a different northern Monterrey neighborhood. There was no known motive for the attack. A fourth unidentified victim was found shot in the head, his body decomposing, in south Monterrey.

Two other men, Oscar Ivan de Leon and Esteban Rubio, were killed that day because they allegedly cut off another car. The transgression led to a verbal exchange before the men in the other car got out, robbed and then shot the men at point blank range. Rubio died at the scene; Ivan died at the hospital.

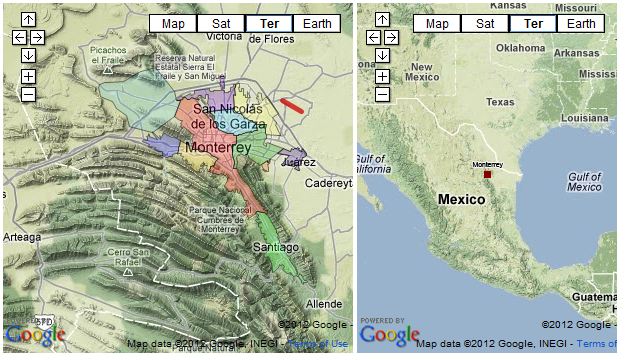

January 16 provides a window into the multiple levels on which the fight for this area is taking place. (When I speak of Monterrey or the area, I am talking about "Metropolitan Monterrey," which, as defined by the government statistical body INEGI, includes the municipalities Apodaca, Garcia, General Escobedo, Guadalupe, Juarez, Monterrey, San Nicolás de los Garza, San Pedro Garza Garcia, Santa Catarina, and Santiago.) On one level, the two largest organizations, the Zetas and Gulf, appear to be fighting for control of the local drug trafficking industry, the most lucrative business in the city. In a way, the Zetas’ rivals are taking a page from the Zetas’ playbook. They identify the tienda, or drug distribution point, then organize and execute an attack.

The attack on Zuniga’s alleged drug shop was typical: fast and with overwhelming force. The impact of such attacks is multiple. They eliminate, for a time, a source of income for the Zetas. They also send a message to other contract workers that their bosses cannot protect them. However, unlike the Zetas, the rivals do not assume control of the “tienda,” or drug distribution center. Instead, they appear to be more like guerrilla assaults, aimed at disruption of services and psychological impact.

The next two murders appear to be attempts by one rival to eliminate the other’s infrastructure. As it is with most murders in the area, little is known about the motives. However, the ways the men were killed – one with an AK-47 at point blank range, the other with a bullet to the head – are classic methods of assassination. This nearly constant tit-for-tat leaves victims scattered throughout the metropolitan area. The victims appear to be mostly contract workers – hired guns, hawks or messengers.

Rubio and Ivan appear to be civilian victims. The two men committed two fatal errors. First, they were driving in a large vehicle, described by the press as a “Ford truck.” These large vehicles draw attention because they are used by both sides of the battle. At one point, the gangs drove them in large caravans, but this led to ambushes and skirmishes with authorities. Caravans are now less frequent, but the criminal cells still move in groups of five or six in large vehicles. Second, Rubio and Ivan may have “challenged” a similarly large vehicle by cutting it off on the road. The results illustrate just how high tensions are in this city and how little regard is left for life and the law.

Most civilian victims are not caught in the crossfire -- they are targeted. Just three days earlier, authorities located the body of Sergio Ruiz Hernandez, a businessman who was kidnapped on January 5, and held for ransom. The family paid 1.2 million pesos (about $90,000) in the hopes he would be freed. He was found with signs of torture and a bullet hole in the head. Kidnappings in the city continue at record levels. During the first 11 months of 2012, the state government reported 53 kidnappings in Metropolitan Monterrey. This is well below the unofficial number of two or three kidnappings per week.

A War with Many Parts

The Nuevo Leon government has registered 371 homicides in Metropolitan Monterrey through November 2012. (See goverment statistics pdf) This is down from previous two years but still above pre-2009 numbers, when the violence skyrocketed.

Why the fight started is worth reviewing. Once the Zetas settled into Monterrey after their deal with the Beltran Leyva Organization (BLO), they began their systematic extortion of nightclubs, transport companies, casinos, liquor stores and other marginally profitable enterprises in the area. This systematic bleeding of the area was not good business and tensions rose between the Zetas and their nominal masters, the Gulf Cartel. These tensions bubbled over when a Gulf command assassinated Sergio Peña Mendoza, alias “Condor III,” in January 2010. The Zetas demanded Gulf hand over the killers. The Gulf refused. War began.

The Zetas solidified their alliance with the Beltran Leyva Organization. The Gulf reached out to the Sinaloa Cartel and formed what has become known as the “New Federation.” The two newly formed alliances entrenched themselves into their respective strongholds: the Gulf Cartel in Reynosa and Matamoros; the Zetas in Monterrey and Nuevo Laredo; Sinaloa in Durango and Sinaloa. From there, they launched attacks on one another that have played out over numerous state lines. At first, these were large scale, involving convoys of bullet-proof Suburbans, pickups and what eventually became known as “narco-tanques” – dump trucks and other large vehicles that had been converted into Mad Max-like battering rams.

But this all-out war in smaller towns eventually shifted to a lower-intensity conflict in larger urban areas, as we are seeing in places such as Culiacan, Durango, Torreon and, of course, Monterrey. The victims are of the type that died on January 16: a mix of “soldiers” and civilians, some of whom simply crossed the wrong person on the wrong street.

However, the war extends beyond civilians. Foreign anti-narcotics agents and analysts say the Zetas continue to exert control over a number of policemen, traffic cops and other security forces in the Monterrey area. And their enemies are targeting them as well. During the first six months of 2011, for example, 78 security officials were killed in Greater Monterrey, according to a count by the governor’s office. The majority of these were police, but another 21 were transit cops, a sign the rivals were seeking to eliminate the Zetas’ eyes and ears at street level as well as their muscle inside the system.

The state and local governments realize the institution has been penetrated to the core and have tried to purge the police on numerous occasions, but with little success. To cite just a few examples: Monterrey municipal authorities dismissed 410 of 752 police in 2010; in Santa Catarina, authorities dismissed 261 police in October 2011; San Pedro Garza Garcia has dismissed over 200 in recent years; San Nicolas de la Garza has dismissed 129 transit police. The turnover left numerous untrained and untested police in charge, and pushed the corrupt ones directly towards criminal organizations. The deficit of police could be as high as 8,000, according to one recent study by the Tec of Monterrey.

The results of this were perhaps clearest in Garcia, Nuevo Leon, a municipality about 40 kilometers from Monterrey. There then Mayor Jaime Rodriguez, who left office in October 2012, dismissed the entire force of 220 officers and replaced them with mostly military personnel. The reaction was immediate. His top security officer was assassinated the day Rodriguez took office. The attack was the Zetas at their deadliest: the group sprayed the mayor’s house with gunfire in the middle of the night, and then ambushed when the security officer and his men reacted to the attack.

Rodriguez says he subsequently faced down two other attempts on his life, including one in which he and his bodyguards allegedly fended off a multiple vehicle caravan full of gunmen on a Monterrey thoroughfare that snakes around the edge of the city. He blamed all the attacks on some 30 of the 220 policemen that he dismissed.

For the three years Rodriguez held the post, the mayor’s office had an army tank stationed at the entrance to city hall. A half-dozen bodyguards accompanied him throughout the day, most of these also former military. He had a retired military colonel as an advisor, who stayed working with the next administration, and he was training civilians to defend themselves and exercise their right to bear arms. (In Mexico, it is legal to carry up to a .38 pistol.)

“Any criminal that comes into Garcia will have to come in with precaution or fear. The same way we do when we go into their territory,” he told InSight Crime.

The Fight for the Prisons

The battle for Monterrey has since moved to the jails where Zetas, Gulf and other criminal groups fight for control. Ironically, jails often offer more protection to high-level members who control the guards through a combination of intimidation and payoffs. Inside, they move to consolidate territory on the penitentiary grounds then create command and control centers from which they can coordinate extortions, kidnappings, large-scale theft, and other criminal activities. Their control, in some instances, is absolute: Zetas (and other criminal groups) have been known to leave jail at night to commit assassinations and attacks on rivals.

This control was evident in the recent massacre and mass jailbreak of Zetas from the Apodoca prison on the edge of Greater Monterrey. At least 30 members of the Zetas escaped, including Oscar Manuel Bernal Soriana, alias “El Araña,” the head of the Monterrey “plaza.” Those who stayed behind killed 44 alleged members of the Gulf Cartel with a combination of knives, pipes and bats, among other blunt objects. The escape and massacre happened around 1 a.m. Prison authorities called for assistance after 3 a.m.

The tit-for-tat between these large organizations has since spilled into the countryside again and spread throughout Mexico. From Guadalajara to Culiacan to Veracruz, bodies are appearing en masse, most recently 49 victims found on the road between Monterrey and Reynosa. This next phase appears to include civilians as well as cartel soldiers. No one has been publicly identified from the massacre yet, but a waiter and a student were among the victims in what is believed to be a related massacre of 18 people in Guadalajara. Messages at the spot where the bodies and body parts were found said the attack was retribution for the death of at least 23 alleged Zetas in Nuevo Laredo the week prior in Guadalajara.

The attacks have taken their toll on all of these organizations. Reports from Monterrey say the city is slowly slipping from the Zetas’ control. As evidence of this, analysts cite the group’s increased use of small time, untrained gang members who employ what security officials bluntly call “spray and pray” attack methods, i.e., pull the trigger and hope that you hit the enemy. Garcia officials showed InSight Crime the remnants of one such attack on a public building by presumed “Zetillas.” The bullet pattern moved in a straight line briefly, then rolled up like a small, upside down “U,” then steadied again -- something you would expect from a shooter who was not trained to handle recoil from an automatic rifle.

“This is the thing that they have: a large army of youth who they bring in, who are defending this criminal structure,” Garcia Mayor Rodriguez explained.

But those who say the Zetas are being pushed out of Monterrey seem to be underestimating the schizophrenic nature of this group and what it represents. The Zetas, in the end, are both sophisticated and aimless; they are a mix of professionals and clowns; they are a combination of strategic thinkers and ridiculously short-sighted profiteers. The confusing nature, makeup, and modus operandi of this group keeps authorities and analysts guessing about where it is going next and what form it will take. In the end, though, just where we put the Zetas in the criminal pantheon often reflects more about how we want to see them, than about who and what they actually are.

Claire McClesky and Christopher Looft contributed reporting to this article. Special thanks to Southern Pulse as well for its assistance on this report and coverage of the area.