Compromise on climate change legislation appears to be increasingly likely in Washington. All the stars are aligning in a way that would push a compromise forward: Gasoline prices are high, the Middle East and Venezuela are creating complex challenges for U.S. foreign policy, Nigeria is increasingly chaotic, and scientific findings are accumulating that confirm temperatures globally are indeed rising.

Into this atmosphere comes Earth First!, a group whose name in the past has been synonymous with the term "ecoterrorism" and which now is dedicated to dramatic direct action protest. Promising to block access to refineries, harass executives and otherwise make a lot of noise, Earth First! has formed a coalition -- Rising Tide North America -- that says it will fill a longstanding void in climate change activism. But while the new coalition is bound to make noise over the coming years, its impact on public policy likely will be much smaller than that of contemporary radical direct-action campaigns.

Rising Tide argues that U.S.-based climate change activism is too staid. The coalition's leaders fret that the public debate is dominated by mainstream environmental groups that excel in lobbying strategies, advertising and traditional public relations campaigns. From the Earth First! perspective, these groups do not bring energy or passion to campaigns, and they compromise too readily on important issues. The implicit argument is that rank-and-file Americans -- including grassroots activists -- have never truly engaged on the climate change issue.

This criticism is generally on target. Climate change is a priority concern in most of the industrialized world -- witness the maelstrom of angst this week over the announcement that the European Union's emissions trading system is not working. The United States, by comparison, is a calm backwater as far as this issue is concerned.

The reasons for the split in perspectives are myriad. First, environmentalism is more deeply embedded in the politics of most industrialized countries than it is in the United States. Further, in many countries, concern about climate change is a mark of erudition; in others, it has become a political statement about being different from Americans. Japan, meanwhile, considers itself "home" to the Kyoto Protocol, and expressing concern about climate change is a patriotic issue. Finally and importantly, activists in other countries have done a better job of convincing the public that climate change is a serious matter that requires government action.

The Slope

Within the United States, climate change has traveled an unusual path in the public policy cycle. It did not follow the typical route from obscurity to the public mind as similar issues do, and as a result, certain attributes are missing from the debate -- including strong grassroots support for federal action on climate change.

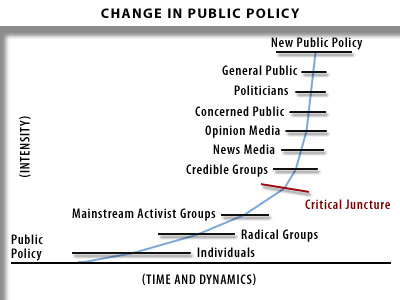

Usually, a policy issue travels a predictable path -- from a raw idea, issue or concern to a mature policy issue that is ready for political attention.

In the initial stages of the cycle, a concept usually is driven by an individual or small group. It is articulated in different ways by various small organizations -- often by groups deemed "radical" by the general public -- until it becomes a concern for larger activist groups that have attained a certain level of credibility with the public. Over time, the issue becomes appealing to increasingly credible nongovernmental organizations, and ultimately to groups that are not necessarily viewed as activist. Once credible nonactivist organizations have embraced the idea, it moves into the mainstream -- where public policy is debated and eventually formed.

Once the issue is articulated in such a way that the public understands the problem, its causes and possible resolutions, time becomes short for those who want to help shape how the final policy is made. Lobbyists and public-relations professionals begin to work in earnest to promote the issue or to defeat it. They excel at framing issues and selling ideas to the mainstream public. And though such professional actors may indeed be passionate about various causes, they do not bring the same type of energy to the debate as do the grassroots activists who fought to bring the issue to the public's mind.

It is significant that, if an issue follows this natural evolution from the fringes to the mainstream, its importance over time does not dissipate among the grassroots activists who initially put energy, sweat and time into making the issue an important popular concern. True, at the end of the process, grassroots activists often might feel "sold out," since the professional lobbying groups in Washington inevitably must make trades and concessions to get a policy passed that addresses the issue. However, the groups at the negotiating table are quite aware of the grassroots pressure in the public, and -- while compromise is necessary -- the stronger the grassroots support for a policy, the more difficult it is for key demands to fall victim to compromise.

Fast-Tracked

In the United States, the climate change issue skipped this typical cycle.

Climate change began as a concern for a few scientists and environmentalists, and then it was an issue promoted by the most credible national environmental groups. Because of this, it did not have to be articulated to grassroots environmentalists or to local activist groups in a compelling way. Thus, grassroots activists were never challenged to consider whether climate change was an issue worth sacrificing for or worth fighting about. The issue became (and largely remains) a priority concern for only a portion of the environmental movement.

There are historical reasons for this.

With the creation of a national environmental movement in the late 1960s, environmentalism in the United States focused mainly on pollution. The national movement -- typified by groups such as Environmental Defense (founded as the Environmental Defense Fund) and Natural Resources Defense Council -- established large offices in Washington to lobby for enforcement of the new Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, to litigate under the citizen-suit provisions of these laws and to fight for the passage of similar laws.

Their success brought increasing numbers of environmental groups to Washington. Over time, the environmental lobby became an institution in Washington -- much like labor, the Chamber of Commerce and other interests.

Climate change became a concern among a few activists in the mid-1980s, and the issue almost immediately found a ready audience among the most credible environmental groups in the country. Anti-pollution activists, who long had been concerned with the ecosystem damage from oil exploration, the air pollution from refineries and the ecological impacts of burning oil and coal, determined that climate change held great promise as a policy issue.

Environmentalists' reactions to the early climate change discussions were clearly articulated by then-Sen. Timothy Wirth, D-Colo., in a 1988 speech before the Senate: "What we've got to do in energy conservation is to try to ride the global warming issue. Even if the theory of global warming is wrong, to have approached global warming as if it is real means energy conservation, so we will be doing the right thing anyway in terms of economic policy and environmental policy." Thus, from the earliest stages of the discussion, the prevailing view among groups concerned about energy conservation, air pollution and offshore oil production was that action to stop climate change -- whether necessary or not -- entailed doing environmentally beneficial things. It was a powerful tactic, regardless of whether the science bore out concerns for the climate in the end.

In other words, climate change policy has been a project of the staid Washington environmental lobby almost from the beginning, and the rapid adoption by the mainstream meant that the standard policy development process -- which entails years of debate and campaigning -- was curtailed.

But on the flip side of the equation, climate change activists never were required to capture the imagination of the public or encourage grassroots environmentalists to get involved in order to bring attention to the problem. People were not needed to hold signs outside power plants and refineries; there was no need for massive letter-writing campaigns to newspaper editors or news networks. Without grassroots involvement in the promotion of the issue, the media -- particularly local media -- never were forced to take a hard look at the issue. In short, political action on climate change was never contingent on people becoming passionate about it; attorneys at Environmental Defense (and other large groups) had it under control from the beginning.

Bringing Grassroots Pressure to Bear

Enter Earth First!, which in forming the Rising Tide coalition has tacitly acknowledged that passionate grassroots interest in climate change policy is still missing. By taking action at this time, the group is signaling a fear that climate change will be treated in Congress as an issue on which easy compromises are possible. The types of compromises that can easily be envisioned -- for instance, trading higher CAFE standards for offshore oil drilling, or nuclear energy for biofuels -- are seen as weakening climate change policy. Rising Tide North America seems to believe that through direct action protests and direct corporate campaigns, the group can make it more difficult for political leaders to compromise on key issues.

It probably cannot. The weakness with climate change policy ultimately is not merely the lack of direct action, but that climate change did not go through the normal trials and tribulations. On most legislation, a congressman's constituents fight over the issue for years before a single lobbyist shows up at the congressman's office. When confrontational direct action crops up at the end of the policy cycle rather than the beginning, it is much more likely to read as opportunistic than sincere.

In the final analysis, climate change appears ready for political action, but the proposals that succeed in Washington likely will not reflect a significant change in U.S. policy. Instead, they will reflect the simplest compromises available to policymakers who are trying to juggle varied special interests, weighty economic issues and environmental concerns.